Of the 2,308 homeless New Yorkers present during the city’s encampment sweeps over more than eight months in 2022, only three people—about 0.1 percent—had accepted shelter and subsequently landed in permanent housing as of January, according to an audit from Comptroller Brad Lander.

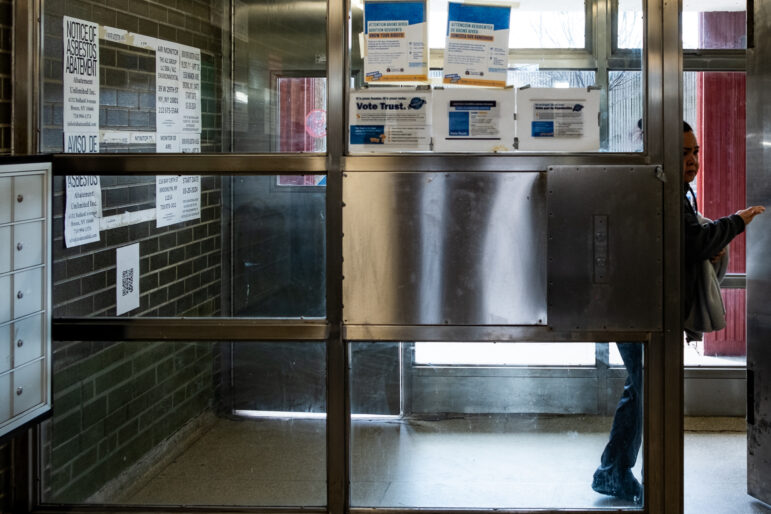

Adi Talwar

New Yorkers experiencing homelessness were camping out on a Lower Manhattan sidewalk near Tompkins Square Park until the city cleared the site during a “clean up” in November 2022.

Of the 2,308 homeless New Yorkers present during encampment sweeps over more than eight months in 2022, only three people—about 0.1 percent—had accepted shelter and subsequently landed in permanent housing as of January*, according to an audit from Comptroller Brad Lander.

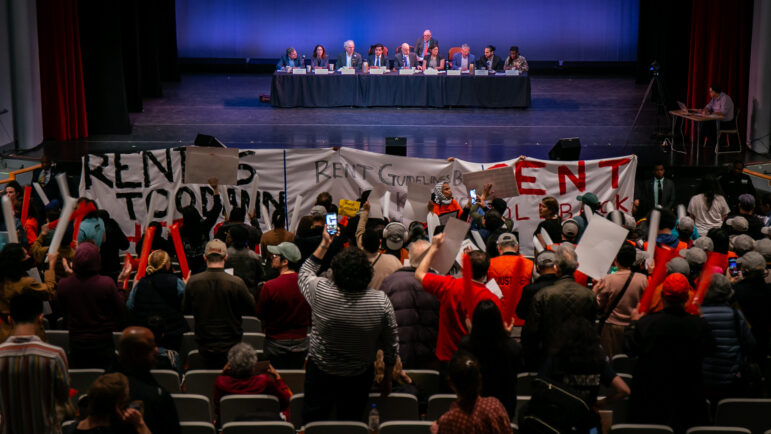

“That is what we call in the business, a policy failure,” Lander told reporters at a press conference releasing the findings Wednesday morning in Tompkins Square Park.

The audit focuses on the role of the Department of Homeless Services, or DHS, in an interagency effort that Mayor Eric Adams launched in March 2022, coordinated with the New York City Police Department, Department of Sanitation and Department of Parks and Recreation. Prior to Adams, former mayor Bill de Blasio also oversaw hundreds of sweeps, or cleanups, annually.

The Adams administration has touted its effort as a way to clear encampments from parks and sidewalks—often in response to complaints from the public and city officials—while connecting street homeless people with shelter and services.

Yet the Comptroller’s findings suggest meager results on both fronts. Of the 2,308 people the city encountered across more than 2,100 cleanups between March 21 and November 30 of 2022, just 119 people accepted shelter. And of those, only 90—fewer than 4 percent—stayed in shelter for more than a day.

Lander’s office reviewed the status of that group of 90 as of late January of this year, and found that 47 people remained in shelter, while just three had been placed in permanent housing. The analysis required reviewing individual case files, according to Maura Hayes-Chaffe, deputy comptroller for audits.

As for the swept areas, auditors visited 99 previously-cleared sites on April 12 of this year, and found that “homeless activity” had returned at or near 31 percent of them. The audit covered sweeps both at larger encampments with physical structures and so-called “pop-ups” where one or more people might stay without comforts like tents or mattresses.

Reached Wednesday, City Hall defended its practices, saying a housing placement for a street homeless person can require time-intensive trust building and casework. “Despite the inherent difficulty of this work, our efforts have been indisputably successful,” a spokesperson said.

The city added that it does not consider the rate of reestablished sites a failure, in part because certain locations remain popular over time due to characteristics like sidewalk sheds.

A total of 156 people accepted shelter placements from encampments in the first year of Adams’ initiative, according to City Hall, compared to just 26 in the year prior, which overlapped with the end of the de Blasio administration. Taking a longer view beyond the audit time frame, 181 people accepted placements between mid-March 2022 and May 31 this year, the city said.

In a letter responding to Lander’s initial findings, Deputy DHS Commissioner Christine Maloney also noted that DHS is not the lead in the encampment cleanup initiative and does not control its partners’ policies.

“Our agency’s intention, of course, is that each individual avail themselves of our services; however, under current law and regulations, DHS can only offer services and must respect the wishes of individuals who decline,” the letter continued.

Recommendations for DHS in Wednesday’s audit include collecting aggregate data on cleanups beyond the number of people present during a sweep and the number who accept shelter referrals, including subsequent shelter entrances and exits.

In response, the agency said it is exploring updating its StreetSmart system to provide aggregate reports on sweeps.

Also on Wednesday, Lander urged the administration to establish a large-scale “Housing First” program, which could help street homeless New Yorkers, often those with mental health or substance use struggles, access apartments without first passing through shelter or accepting mandatory services.

Last November, Mayor Adams announced a pilot program with Volunteers of America-Greater New York (VOA-GNY) aimed at moving 80 street-homeless New Yorkers into apartments. As of May, City Limits reported that 66 people had moved in, following one or two weeks on average at a welcome center. Lander described the effort Wednesday as an encouraging step.

In a statement, City Hall said it is “glad to hear that the comptroller agrees with us on the importance of innovating to get more people housed faster,” adding that the VOA-GNY program “has already placed nearly 80 New Yorkers experiencing homelessness directly from the street into an apartment.”

But Dave Giffen, executive director of Coalition for the Homeless, called for a deeper investment at Lander’s press conference Wednesday, accompanied by an end to sweeps.

“We don’t need more pilot programs, we don’t need more statements of support, we need investment in the solutions that work,” he said.

The Coalition earlier this week released its annual “State of the Homeless” report, giving the Adams administration an “F” for its handling of street homelessness in particular, in part because of the mayor’s aggressive sweeps policy, which Giffen said erodes homeless New Yorkers’ trust in the city and makes it less likely for them to accept placement.

“It made it much harder for those that are actually trying to help those living on the streets to come indoors,” Giffen told City Limits, noting that many sweeps end with the unhoused person’s belongings being thrown away by police or sanitation workers.

Crystal Vails, a member with the Safety Net Project, has been homeless for 13 years, though she now has a lead on an apartment in Queens with the help of a city-issued rental voucher. Vails has developed strategies to avoid sweep teams in Manhattan. “When I see the trash truck, I know they on their way,” she told City Limits Wednesday.

Nevertheless, she said she’s been swept multiple times this year, and the experience is stressful. As soon as it’s over, she returns to her preferred spot. “I’d rather have an apartment,” she said. “The shelter sucks. And it’s too damn nasty. Nasty, dirty and filthy.”

In her letter responding to Lander’s audit, Maloney of DHS emphasized that street homeless New Yorkers make up a minority share of the city’s overall homeless population—6 percent, based on 2022 point-in-time estimates from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, compared to 57 percent in San Francisco and 70 percent in Los Angeles.

“These data points are a reflection of NYC’s right to shelter policies and diligent outreach efforts to unsheltered individuals,” Maloney wrote.

Lander zeroed in Wednesday on DHS’s reference to this “right to shelter” regime, which is unique in ensuring access to a shelter bed, at least temporarily. Recently, the Adams administration has sought to suspend some of these protections in the face of an influx of migrants to the city.

“DHS’s response is a reminder of the critical nature of the right to shelter in dramatically reducing street homelessness in the first place,” Lander said.

*This story has been updated to clarify that housing placements come from the pool of individuals who entered a shelter subsequent to a sweep.